I’ve started using Threads a lot more and answering random questions that come up. The one that seems to come up most frequently and I feel I can never quite do justice to answering in a short thread is “How do I run in zone 2? Whenever I try my HR spikes and I have to walk.”

I start with some background which gets a bit nerdy so feel free to scroll down to “So How Do You Run in Zone 2”.

Some Background

This section was first drafted in November 2024 largely from memory; if anyone wants to correct me, please do and I’ll update it.

I first encountered ‘zones’ when I started taking my self coaching more seriously and picked up Joe Friel’s ‘Triathlon Training Bible’.

For many years I regularly did bike, swim and run tests to find my ‘threshold’ (or Maximum Lactate Steady State – MLSS or LT2) – a pace or power that is either the maximum that you can hold for an hour (the original Andy Coggan definition) or the maximum pace that you can achieve whilst your body can still use all the lactate it produces. They’re not exactly the same thing but the terms are often used interchangeably and for most purposes the two things are close enough to not cause problems if you muddle them up.

Once you have your threshold power/pace you then choose whose zone system you want to use (there are quite a few) and they will tell you what zone corresponds to what percentage of your threshold.

You will notice that I’ve used power/pace and not heart rate; when Andy Coggan did some of the earliest work on this he was using power – but power meters were way beyond the budget of most athletes at the time, so many coaches and authors took the view that you record your heart rate during whichever test protocol you do, because HR monitors were cheap, and then you use that to determine what your threshold is and hence what the other zones are.

Unfortunately HR is also affected by temperature, menstrual cycle and other factors so will vary from day to day for the same lactate level and power/pace.

There is also another important point to be aware of; whilst threshold (MLSS) is a reasonably well understood and known physiological point there is a point that occurs at a lower intensity than this as you increase your pace or power, sometimes know as the aerobic threshold or LT1 – this is the point when the lactate level in your blood begins to rise sharply above your resting level of lactate. Most zone systems just assume that LT1 will sit at a certain percentage of your MLSS – and for many people this is simply not true (in fact this point actually moves upwards far more readily than LT2 as you get fitter, so they tend to get closer together).

You may (or may not) be wondering why lactate level is so significant; at the end of the day lactate is just a chemical that your body produces and uses as fuel – as far as I can establish the reason it is so significant in sports science is that its because it is relatively easy to measure…

So we now have established that you can do a test and get a heart rate (or ideally power / pace) for your threshold and then create some zones to train in. Unfortunately lots of people don’t like doing tests that involve maximal efforts for various durations (understandably), this led to the popularisation of zone systems that were based on your maximum HR – unfortunately this is even more unpleasant to test than your threshold. The outcome was that lots of people end up using zones based on a calculation of maximum heart rate that is 220 minus your age.

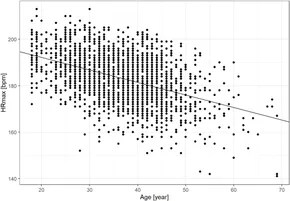

There’s a recent paper “HR Max Prediction Based on Age, Body Composition, Fitness Level, Testing Modality and Sex in Physically Active Population” by Lach et al. that has a lovely illustration of why this is a very bad idea.

I’ll ignore the fact that their data actually ends up with a regression that is more like 202 – 0.5*age and draw your attention to just how far either side of the line the data points spread; whilst 220 – age or 202 – 0.5 age might give a good estimate for the average max HR of any population it is going to have an error of plus or minus 20 for any individual.

So if you take your heart rate zones based on 220 – age then your zones could be more than 20 bpm too high or too low!

Now we have some understanding of what zones are, we need to consider what is this magic ‘zone 2’. Whilst I don’t have a definitive history of zone 2 training I am reasonably confident in saying that one of the early proponents of ‘polarised training’ (doing most of your training ‘easy’) is Stephen Seiler and his work on the ’80:20 rule’, i.e., you do 80% of your training easy and 20% hard. I’m going to paraphrase a lot of research and writing and say that in endurance sport the best predictor of fast times is lots of volume (time multiplied by intensity) and the best way to get lots of volume is to do lots of training at the highest intensity that you can do without over-training or getting injured.

Here we reach the crux of it; zone 2 training is all about doing the most training you can without getting injured or ill and for many people that is suggested to be achieved by running just under LT1 – which is the upper boundary of zone 2 in most zone systems.

Unfortunately most methods of working out your zones are hard work and don’t give a particularly accurate heart rate for zone 2 and some of the methods (220 – age, I’m looking at you) are wildly inaccurate for most people.

Also a thanks to Kolie Moore and his Empirical Cycling podcast (https://www.empiricalcycling.com/) a lot of my recent thinking on this topic has been inspired by his podcasts.

When I’m coaching my athletes I’ve become much more focused on setting their workouts so they are either working below LT1, around LT2, near VO2 Max (the pace/power at which your body’s oxygen consumption peaks) or sprints and working with them to try and hit the correct paces and powers by perceived exertion (how hard it feels) whenever possible – we then tend to look at pace, power and heart rate after key workouts to see how their performance is progressing.

So How Do You Run In Zone 2?

To summarise the previous section quickly; the top of ‘zone 2’ or ‘easy running’ is the level of exertion that corresponds to your body starting to use more of its various different energy systems. Staying below this level for most of your running should allow you to spend more time running and less time injured or ill. The pace at which this level occurs will vary slightly from day to day and hugely with terrain or climactic conditions. Whilst HR is often used to find this level it varies from day to day and the methods of calculating it vary from somewhat dubious to wildly inaccurate.

Without a shadow of a doubt my favourite method to get ‘easy running’ right is to go for a run with someone else, ideally a friend but a bitter enemy would work just as well, and make sure that you can engage in a flowing conversation. If you have to pause the conversation to get your breath back then you are going too fast. If you prefer to run alone or don’t have the option of finding a local running group then you could wear some running headphones and phone a friend.

If the conversation test isn’t for you then maybe the singing test would work better – exactly as it sounds; if you can sing when you’re running then you’re almost certainly in the right zone.

The final option that I find works well for some people, but not everyone, is whether you can breathe through your nose. You don’t need to spend your whole run breathing solely through your nose, but if you’re able to breathe through just your nose for two or three minutes then you’re almost certainly ‘easy running’ or in zone 2. There are people who can’t breath through their nose when sat still so, if this is you, you’ll need to stick with one of the previous methods.

If you do have a heart rate monitor then once you’ve got a feel for ‘easy’ zone 2 running, and I’d suggest that should be at least a year since temperature and clothing will have an impact, you can start to look at your heart rate occasionally after runs. You should find that as you get fitter your heart rate for the same pace will fall; although I have occasionally found that after a key race and a good recovery block that my heart rate AND pace are both higher for the same perceived effort.

It is possible that, for some people, a brisk walk will get you into zone 2 and that’s fine – if this is you then you have a couple of options; if you’re very new to running then use one of the ‘couch to 5km’ apps (I like the NHS one) and that may well be exactly what you need. Alternatively, you could use the ’80:20′ rule (80% of your workouts easy, 20% hard) and do 2-4 brisk walk workouts a week and one run a week – I expect you will gradually find that your brisk walks will become runs. You can also adapt your form a little bit, try taking shorter quicker steps (this also has the benefit of reducing your risk of overstriding and causing yourself injuries).

My penultimate piece of advice is that one of the really big benefits of zone 2 / easy running is that it means that you can (if you want) do 1 or 2 really hard workouts a week and perform really well in them; so don’t think you have to always run ‘easy’.

My final ‘tip’ is that whilst there is an overwhelming amount of evidence about the benefits of easy running – that only means it works for the majority of people, not necessarily everyone. So if you try ‘zone 2 running’ for a few months but find that doing all your runs at a harder effort level works better for you, then that’s fine too – providing its keeping you physically and mentally healthy and you’re enjoying it, then carry on!